Hyaluronidase vs hyaluronic acid

Dr Patrick Treacy looks at the history of hyaluronic acid and how hyaluronidase can correct complications safely and effectively

Hyaluronic acid (HA) and hyaluronidase both hold significant importance in the field of aesthetic medicine, each playing a unique role. A primary component of the extracellular matrix, HA is mainly responsible for maintaining hydration in the dermis. Its unique ability to retain water makes it crucial for keeping the skin hydrated, plump, and youthful. In aesthetic medicine, HA is extensively used in the form of dermal fillers, with its biocompatibility and effectiveness making it a popular choice in non-surgical cosmetic procedures. Hyaluronidase, on the other hand, is an enzyme that breaks down hyaluronic acid. In aesthetic practice, its primary function is to dissolve cross-linked HA dermal fillers. This becomes particularly important in managing and correcting complications or undesired results from HA filler injections, such as overfilling, asymmetry, or lumps. Hyaluronidase can quickly and effectively reverse these effects, providing a safety net for both practitioners and patients. It can also be used in certain cases to improve resistant oedema or to enhance the penetration of local anaesthetics in the skin. This is the story of both chemicals.

THE DISCOVERY OF HYALURONIC ACID

In 1934, while Nazi Germany and Poland were signing a 10-year nonaggression treaty, Germans Karl Meyer and John Palmer wrote in the Journal of Biological Chemistry about an unusual polysaccharide with an extremely high molecular weight isolated from the vitreous of bovine eyes. Meyer was born in the village of Karpen, Germany, near Cologne. In 1917, he was drafted into the German army and served in the last year of World War I. After the war, he entered medical school at the University of Cologne and received a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1924. He then went to Berlin for a year of study in medical chemistry and met several promising young biochemists, including Fritz Albert Lippman, Ernst Chain and Hans Adolf Krebs.

Sir Hans Krebs

Krebs was born in Hildesheim, Germany. In June 1933, the National Socialist Government terminated his appointment, and he went to the School of Biochemistry, Cambridge, where he researched the complex chemical processes that provide living organisms with high-energy phosphate by way of what is known as the Krebs or citric acid cycle. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1953 was divided equally between Krebs ‘for his discovery of the citric acid cycle’ and Lipmann ‘for his discovery of co-enzyme A and its importance for intermediary metabolism’. Chain was another German-born British biochemist, who became a 1945 co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his work on penicillin.

Meanwhile, Meyer decided, no doubt in part because of the rising anti-semitism in Europe and the increasing probability of war, to go back to the US. He received a position as an assistant professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. In part because of the mission of his department, Meyer began to study the lysozyme present in tears and undertook to identify a physiological substrate for the enzyme.

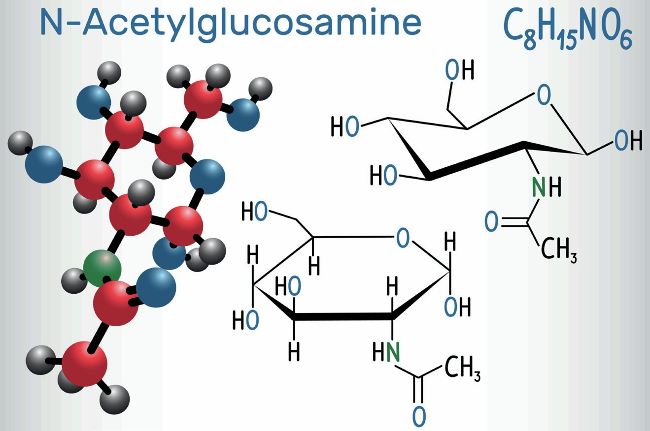

Examination of the viscous vitreous humour of the eye as a plausible source of substrate quickly led to the discovery of hyaluronan, which is reported in this Journal of Biological Chemistry (JBC) classic. While there, Meyer and his assistant, Palmer, isolated a novel, high molecular weight polysaccharide and reported that it was composed of ‘an uronic acid and an amino sugar’.

Being the first to mention it, they gave the new substance the name ‘hyaluronic acid’ (the modern name ‘hyaluronan’) derived from ‘hyaloid’ (glass-like in appearance) and ‘uronic acid’ In 1958, Meyer chaired the annual meeting of the American Society of Biological Chemists and stated in his opening remark: “It is my opinion that the mucopolysaccharides will never be a highly popular field in biochemistry, but they will probably not be relegated again to the realms of history.”

How wrong he was; like the Beatles and computers being originally turned down, HA was to become one of the most important chemicals in the world. While Meyer and Palmer are generally considered to have discovered HA, it is fair to mention that as far back as 1918, just as World War I ended, Levene and Lopez-Suarez had isolated a new polysaccharide from the vitreous body and cord blood that they called ‘mucoitin-sulfuric acid’. Over the next decade, Meyer and others isolated HA from various animal organs. It was found to exist in joint fluid, the umbilical cord and, recently, it has become possible to extract HA from almost all vertebrate tissues. Finding a use for HA in medicinal practice did not occur until 1943, during the Second World War. The start of World War II (WWII) led to the deployment of combat troops in several continents and fatalities and casualties among both the military and civilians became an inevitable consequence. A large number of injured people needed life-saving treatment and a speedy return to duty. The Soviet Union, its allies and its opponents had no specialised medical units for patients with burn injuries in military or civilian hospitals when WWII began. Intensive studies of the specific issues of diagnosis and treatment of thermal and frostbite injury were conducted in the Soviet Union before the war. The first special units for patients with burn injuries were created, and the first specialists received their first clinical experience.

In the 1950s, EA Balazs initiated experiments with HA to investigate its potential as a prosthesis for the treatment of retinal detachment. In 1953, Roseman and co-workers published an article in which they described the precipitation of HA from the cultural liquid (CL) of Group A streptococcus. In 1970, hyaluronan was first injected into the joints of racehorses that suffered from arthritis with a clear and positive outcome observed. In 1982, R. Miller started to use HA in implanted intraocular lenses. In 1996, when Mad Cow Disease hit Britain, causing the mass slaughter of herds of cattle and new laws to stop beef being sold on the bone, a Swedish company called Q-Med released to the world non-animal stabilised HA (NASHA) technology. For the first time, hyaluronic gel particles within a viscoelastic medium, subjected to a physiological salt solution, could be used as a soft-tissue augmentation facial implant. The process was invented by Bengt Ågerup, who was born in Uppsala (1943) and studied renal physiology at a university there. He had previously worked for many years as a researcher at Pharmacia. In March 2011, he sold his shares in Q-Med to Galderma SA, a French-Swiss pharmaceutical company. In 2018, a breakthrough skin treatment called Profhilo was developed by IBSA, which introduced a new category in the injectables market – bio remodelling. It is an injectable, stabilised HA-based product, produced without the use of chemical cross-linking agents (BDDE) according to a patented technology (NAHYCO), designed to remodel multi-layer skin tissue. Since these ground-breaking cases, hyaluronan has become one of the most important components in ophthalmology and has found extremely wide applications in aesthetic medicine.

THE DISCOVERY OF HYALURONIDASE

Hyaluronidase has a history of medical use spanning over six decades. The enzyme has received approval for several specific medical purposes, including enhancing the effectiveness of drug delivery by promoting better dispersion and absorption of injected substances. Its role in aesthetic medicine, particularly in addressing complications from HA-based dermal fillers, has become increasingly important. Historically, medical hyaluronidase was extracted from bovine or sheep testicles and used without purification. This practice was typical until more advanced and purified forms of hyaluronidase were developed. In 1971, Meyer found three types of hyaluronidases, testicular-type hyaluronidase or hyaluronoglucosaminidase leech hyaluronidase or hyaluronoglucuronidase (EC 3.2.1.36, hyaluronate 3-glycanohydrolase) and microbial hyaluronidase or hyaluronate lyase. He classified hyaluronidases into three categories according to its mechanism of action. In 2004, Cheong cloned and molecular characterised the first aquatic hyaluronidase, SFHYA1, from the venom of stonefish. Encoding the precursor of this enzyme was isolated from a cDNA library prepared from stonefish venom glands. These enzymes, prevalent in snake venoms, play a crucial role in breaking down hyaluronan, within connective tissues. Termed ‘snake venom hyaluronidases’ (SVHYA), they aid in the destructive process during snake bites by facilitating venom dispersion through tissues. Interestingly, these enzymes share notable similarities with their mammalian counterparts, the hyaluronidases (HYAL). Both SVHYA and HYAL target hyaluronan, resulting in the formation of low molecular weight HA fragments (LMW-HA). The LMW-HA fragments, produced because of hyaluronidase activity, activate various signalling pathways. This activation leads to several immune responses, which I believe leads to delayed tissue nodules (DTNs) after dermal fillers are broken down in the body and increased production of interleukins, upregulation of chemokines, activation of dendritic cells, and proliferation of T cells. These processes form part of both the innate and adaptive immune responses. Hyaluronidase is employed in various other ways. Its ‘off-label’ uses encompass dissolving HA-based fillers, treating granulomatous foreign body reactions, and addressing skin necrosis related to filler injections. I have recently been credited in an article from the LA Times with introducing the enzyme hyaluronidase to aesthetic medicine, and its exponential use by cosmetic doctors worldwide. Hyaluronidase now plays a pivotal role in aesthetic medicine, primarily due to its dissolving properties that effectively address complications from HA-based dermal filler injections. Its importance is underscored when fillers result in undesired effects or complications, often entering blood vessels and causing irreversible skin necrosis and cell death. This innovation allows aesthetic practitioners to correct these issues safely and effectively.

Awards for hyaluronidase

DR PATRICK TREACY

Dr Patrick Treacy has been credited with being among the first doctors in the world to use hyaluronidase in aesthetic medicine and has been awarded for this significant contribution to the industry. He recently was invited to speak in Monaco about the discovery of both HA, and hyaluronidase, and his story of helping to bring this important enzyme into this field of medicine. He remembers helplessly contacting QMed the original producers of HA fillers about what doses to use, treating Michael Jackson as the first patient in the United States when he wanted to have fillers removed from his face before he met the Queen. He also recalls trying for years to convince his American colleagues they were using far too low doses of hyaluronidase to treat vascular occlusions before his method, which was called ‘The Treacy Protocol’ in Eastern Europe became globally established.