DERMOSCOPY

DERMOSCOPY OF MELASMA: A DIAGNOSTIC AIDE

Consultant dermatologist Dr Rajani Nalluri and Brittani Jones consider how to improve and refine melasma diagnosis by identifying structures on dermoscopy that are associated with the condition

The use of dermoscopy is becoming increasingly pervasive within dermatology to improve diagnostic accuracy and, in some instances, avoid unwarranted biopsies and other invasive procedures. Additionally, it can be used to monitor the progression, improvement, or worsening, of differing cutaneous conditions. However, efficient integration of dermoscopy into clinical practice not only requires training and practice, but also an understanding of the unique dermatoscopic features characteristic of each condition. Melasma is an acquired disorder of pigmentation that has a predilection for skin of colour patients, namely women of reproductive age. It presents as hyperpigmented macules and patches in sun-exposed areas of the skin, primarily facial. Although largely asymptomatic, melasma can be burdensome psychologically, thereby underscoring the need for early detection and diagnosis in addition to improved therapeutic options. This article aims to help improve and refine melasma diagnosis by identifying various structures on dermoscopy that are associated with the condition.

INTRODUCTION

Women of colour presenting with new onset facial hyperpigmentation during hormonal contraceptive use or pregnancy should generate concern for melasma, a common skin pigmentation disorder. However, melasma is not limited to this group, as it can be a chronic condition lasting decades and may affect men as well.1 An acquired pigment disorder characterised by symmetric brown macules and patches with variability in the degree of saturation, melasma occurs primarily on sun-exposed areas of the skin.2-6Its prevalence ranges from 1.5%-33.3%, with a greater number of affected individuals being women of reproductive age and individuals of Hispanic, East Asian, Indian, Middle Eastern, and African-Mediterranean descent. 3,7,8Research is looking into the genetic foundation of melasma, and several immunochemical features have been implicated in its pathogenesis. Proteins such as vascular endothelial growth factor and inducible nitric oxide synthase, the non-coding H19 RNA molecule, and activity within the Wnt pathway have been shown to play a role in melasma.2,7,9Additionally, melasma is associated with several inciting factors, such as sun exposure, pregnancy, use of oral contraceptives, and thyroid dysfunction. 2,3,6-10Facial melasma can be classified according to the pattern of distribution (centrofacial, malar, and mandibular) or by the depth of pigment (epidermal, dermal, and mixed subtypes). 3,6-8

Melasma is generally asymptomatic; however, the psychological association of melasma with feelings of embarrassment, frustration, negative perception of appearance, and impaired interpersonal relationships has been established, signifying the need for improved diagnostic means, treatments, and continued research.7

Early diagnosis allows for timely treatment, improved quality of life, and prevention of the development of dermal melasma, which is more difficult to treat. Although diagnosis is straightforward, melasma can sometimes be difficult to differentiate from other facial pigmentary disorders. Skin biopsy as a means of diagnosis is not preferable, because of possible scarring on the face. Using dermoscopy, a noninvasive method that mitigates scarring and aids in diagnostic accuracy, could therefore improve patient outcomes and satisfaction.

DERMOSCOPY FOR DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF MELASMA

The increasing utility of dermoscopy in diagnosing melasma can be partially attributed to its ability to visualise and magnify structures throughout the epidermis and the superficial layers of the dermis that are not visible to the unaided eye.11-13The nonpolarised light contact dermatoscope enhances the appearance of skin structures via the use of a glass plate and interfacing liquid, which manipulates the skin’s propensity to reflect light. The polarised light non-contact dermatoscope uses polarised light and cross-polarised filters to visualise skin structures. 13The polarised light non-contact instrument may be better for visualising vasculature because it does not require a compressive force, whereas the nonpolarised light contact instrument may be better for visualisation of more superficial structures. 11,13Using the dermatoscope to characterise the morphology of vasculature, scaling, colours, follicles, and other intrinsic features, in conjunction with a patient’s history and clinical picture, can promote refinement of diagnosis, and this approach can help differentiate between melasma and other conditions that have a similar presentation, including exogenous ochronosis. 11,12

The Wood’s lamp was the previous standard for diagnosing melasma. Research has revealed limitations to that modality, namely, its inability to discriminate between epidermal, dermal, and mixed subtypes of melasma.1,5The hue of melanin as it appears on the dermatoscope correlates with the skin layers, which appear black/dark brown within the stratum corneum, brown throughout the epidermis and superficial dermis, and blue-grey in the deeper dermis, further helping to categorise melasma. 3,13

FEATURES OF MELASMA UNDER THE DERMATOSCOPE

Dermoscopic features of melasma include the following (Figure 1)2,4,7,9,10,14-18

• Accentuation of a fine pseudoreticular pigment network superimposed over a light-brown amorphous region

• Sparing of follicular and sweat gland openings

• Increased vascularity and the presence of telangiectasias

• Brown granules and globules

• Annular and arcuate structures

Dermoscopic features that help to identify the depth of pigment include the following (Figure 2)1,5,10

• Epidermal: light brown homogenous pigmentation with areas of sparing and regular pigment network

• Dermal: uniform grey-brown or grey-black pigmentation, no areas of sparing, irregular pigment network, arciform structures, and telangiectasias

• Mixed: diffuse reticular pigmentation of brownish or greyish black patch

DISORDERS SIMILAR TO MELASMA

Several skin conditions may appear similar to melasma, including exogenous ochronosis, a condition mediated by long-term topical steroid use. Exogenous ochronosis is characterised by blue-grey nebulous areas when viewed with the dermatoscope and may show damage to follicular openings, as well as irregular, brown-grey globular, annular, or arciform structures.4Akin to melasma, lichen planus pigmentosus, an uncommon variant of lichen planus, is likewise a pigment disorder primarily affecting skin of colour. Dermatoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus include grey-blue globules, deposition of grey-blue brown pigment in perifollicular or peri-eccrine areas, a hem-like pigment pattern, and the absence of Wickham striae. 4Pigmentary demarcation lines that denote transition between differing skin tones can be difficult to distinguish from melasma since they have a similar time of onset in puberty and in pregnancy and can have a similar dermatoscopic appearance involving a prominent or exaggerated non-uniform pseudoreticular pattern. 4

CONCLUSION

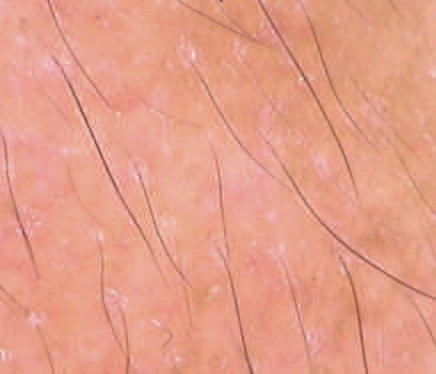

In addition to improving the diagnosis and prognosis of melasma, dermoscopy can aid in assessing treatment efficacy and monitoring the development of complications such as atrophy, telangiectasias, and ochronosis.12In one of our patients with melasma, dryness, scale, and erythema were also visible, indicating possible irritating effects of topical treatments, which can be monitored with the dermatoscope (Figure 3). For the aforementioned reasons, we advocate for the expanded use of dermoscopy for the diagnosis and surveillance of melasma and other pigmentary disorders.

FIGURES

Figure 1. Dermoscopic features of melasma: pseudoreticular network (yellow arrow), telangiectasia (red arrow), sparing of pseudoreticular area (black arrow), arcuate structures (green arrow), brown granule (blue arrow).

Figure 2. Mixed melasma showing dark brown dermal component with no area of pairing (dark brown circle) and light brown epidermal component ( yellow circle).

Figure 3. Erythema and scale in a patient who developed irritant reaction to combination cream.

REFERENCES

1. Dharni R, Madke B, Singh AL. Correlation of clinicodermatoscopic and Wood’s lamp findings in patients having melasma. Pigment International. 2018;5:91-95.

2. Sarkar R, Arora P, Garg VK, Sonthalia S, Gokhale N. Melasma update. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:426-435.

3. Mayeaux EJ, Usatine RP. Melasma. In: Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, eds. The Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1303-1307.

4. Chatterjee M, Neema S. Dermoscopy of pigmentary disorders in brown skin. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:473-485.

5. Manjunath K, Kiran C, Sonakshi S, Ashwini N, Ritu A. Comparative study of woods lamp and dermoscopic features of melasma. Journal of Evidence Based Medicine and Healthcare. 2015;2:9012-9015.

6. Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of colour. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(1 Suppl):S21-S37.

7. Grimes PE. Melasma: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and diagnosis. In: Dellavalle RP, Alexis AP, Corona R, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: Wolters Kluwer; 2019. Available at https:// www.uptodate.com/contents/melasmaepidemiology-pathogenesis-clinicalpresentation-and-diagnosis. Updated March 30, 2021. Accessed September 14, 2020.

8. Rodrigues M, Pandya AG. Hypermelanoses. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al., eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2019:1351-1390.

9. Khunger N, Kandhari R, Singh A, Ramesh V. A clinical, dermoscopic, histopathological and immunohistochemical study of melasma and facial pigmentary demarcation lines in the skin of colour. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14515.

10. Nanjundaswamy BL, Joseph JM, Raghavendra KR. A clinico dermoscopic study of melasma in a tertiary care center. Pigment International. 2017;4:98-103.

11. Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: a practical overview. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:471-507.

12. Gupta T, Sarkar R. Dermoscopy in melasma − is it useful? Pigment International. 2017;4:63-64.

13. Marghoob AA, Jaimes N. Overview of dermoscopy. In: Tsao H, Corona R, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: Wolters Kluwer; 2019. Available at https://www.uptodate. com/contents/overview-of-dermoscopy. Updated September 9, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2020.

14. Shanavaz AA, Bathina M, Amin VB, Pinto M, Manjunath SM. A clinical and dermatoscopic study of melasma. IP Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2020;6:50-56.

15. Berman B, Ricotti C, Viera M, Amini S. Differentiation of exogenous ochronosis from melasma by dermoscopy [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(3 Suppl 1):AB2.

16. Khunger N, Kandhari R. Dermoscopic criteria for differentiating exogenous ochronosis from melasma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:819-821.

17. Sarkar R, Ailawadi P, Garg S. Melasma in men: a review of clinical, etiological, and management issues. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:53-59.

18. Sonthalia S, Jha AK, Langar S. Dermoscopy of melasma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:525-526.